Development, disease ravages regional citrus industry

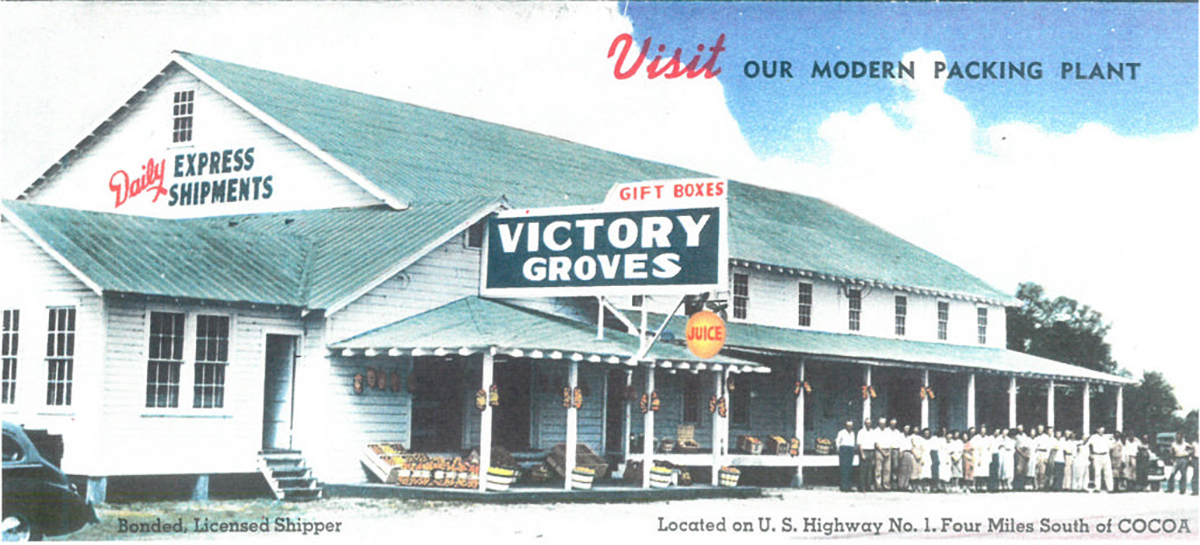

Among his birthday presents last year, Frank Sullivan III found a very special one: a wooden board. Mind you, this was no ordinary wood, for it was plucked from the demolition of the Sullivan Victory Groves packinghouse in Rockledge, an iconic building that for decades was representative of the once-robust citrus industry in Brevard.

Sullivan had been there as the wrecking ball eradicated history.

“It was very hard to watch, but the packinghouses are a thing of the past, as is the citrus industry in this area,” the 84-year-old said.

Hobby farmer Jerry Hunt cares for the hundreds of trees in his Merritt Island grove. JASON HOOK

Disease and development have forever changed the landscape of Brevard, once redolent with the fragrance of orange blossoms that promised the gustatory delights of Indian River fruit, prized above others as the king of oranges.

SELLING BETTER OPTION

Citrus diseases such as canker and greening walloped the Florida citrus industry, but in Brevard, growers also had to cope with the undeniable fact that land was worth more for development than for agriculture, that more — and easier — income could be realized from selling sickly groves than from trying to save them.

Harvey’s Groves, once a major Space Coast citrus producer, shut its packinghouse doors in 2017. JASON HOOK

“When I first got started, Brevard had 29,000 residents,” Sullivan said. “Now we’re closing in on 700,000.”

Suntree resident Joyce Wilden grew up on her family’s 80-acre farm in Micco. While her parents did not grow citrus, the farm was bordered by citrus groves.

“We used to ride the horses through the groves all the time and one of the grove owners let us pick whatever we wanted for our own consumption,” Wilden said.

The groves were long ago replaced by a housing development.

Sullivan, a third-generation citrus grower, witnessed the end of an era with the demolition of the Sullivan Victory Groves packinghouse last year.

GROWING NO MORE

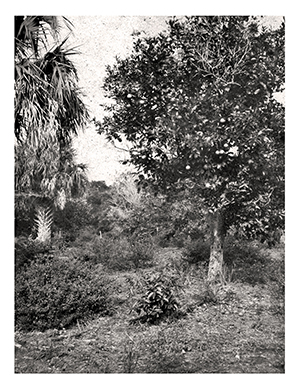

Although the south end of the county boasted a fair amount of groves, it could never compare to Merritt Island and Cape Canaveral, once the heart of Brevard’s citrus production. Douglas Dummett’s Merritt Island grove, which survived the devastating freeze of 1835, saved the industry after Dummett distributed cuttings and seeds to growers around the state.

Douglas Dummett’s orange grove on Merritt Island is considered the mother grove for all current citrus in Florida. Cuttings and seedlings from the grove saved the industry after it was decimated by a freeze in 1835. BREVARD COUNTY HISTORICAL COMMISSION

“Back in the day, most of Merritt Island was citrus,” Sullivan said.

The fate of Sullivan Victory Groves reflects the industry’s health. Sullivan, a third-generation grower, once provided juice manufacturers — and orange-loving consumers worldwide — with thousands upon thousands of boxes of oranges, each weighing in close to 100 pounds.

Freezes in 1983, 1985 and 1989, when temperatures hovered at 17 degrees for hours, walloped Victory Groves, as it did all the groves in Brevard. Then came the canker, a citrus disease that blemishes the fruit but does not affect the flavor of the juice. At least the oranges could be salvaged for juice, but then the groves took another hit with the appearance of greening, which keeps the fruit from ripening, from ever reaching maturity.

By 1991, Sullivan had closed the packinghouse.

“There was nothing to pack,” he said.

Indian River fruit was once so prized and had so many copycats that the appellation is legally permitted to be used only for the fruit grown in a 200-mile strip of land between Daytona Beach and West Palm Beach.

PRODUCTION DOWN

Statewide, the industry remains beleaguered. In 1997, the state produced more than 340 million 90-pound boxes of oranges. The number dropped to 67 million boxes last year, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture data.

Sullivan, the consummate grower, remains active in the industry through a small mail order operation, and he keeps abreast of research that might revive the groves. There have been some promising studies such as the experiment in Polk County to grow citrus under screens. The University of Florida has planted disease-hardy experimental trees on the grounds of Field Manor, the historical Merritt Island home once ringed with groves.

The Dundee Citrus Growers cooperative is encouraging growers to get back in action by loaning them $10 per tree planted, a loan that will be forgiven when the tree bears fruit. In neighboring Indian River County, investors from the United States and abroad have joined forces with commercial growers to help develop 1,500 acres of grapefruit.

The packinghouse of Sullivan Victory Groves was for decades a landmark along U.S. I in Rockledge. BREVARD COUNTY HISTORICAL COMMISSION

ROCKETS WIN OUT

In the Space Coast, however, hopes for an orange renaissance are dim, and the space industry had more than its share in halting the development. Nine thousand acres of prime groves, including Dummett’s historical plantings, once grew in the area NASA deemed a buffer zone for the Kennedy Space Center. Sullivan’s family owned 850 acres there.

The government bought out the owners but allowed them to lease the groves for a few years, until the Department of the Interior decided that the land should revert to native vegetation.

“They told us that citrus was introduced in Florida only in the 1400s and that it did not qualify as native,” Sullivan said.

Frank Sullivan of Sullivan Victory Groves retains a small mail-order citrus shipping operation, but no longer owns any orange groves.

The groves languished and died.

“Now they are overrun with Brazilian peppers,” Sullivan said.

Although not native, citrus has been in America since Christopher Columbus introduced it to the New World in 1493. Ponce de Leon probably planted the first orange trees in Florida and the conquistadors soon noted how well these young transplants grew in Florida’s sandy soil and subtropical climate.

The trees grew wild, but were tamed by post-Civil War growers, transplants who abandoned other southern states for the promise of land in Florida.

Sullivan’s family had grown oranges since 1900, but these days, Sullivan doesn’t own a citrus tree even in his backyard. He still loves orange juice, but he has to buy it at the grocery store, or for a treat, from the Cocoa Beach Winery & Gourmet Market, which carries cold fresh-squeezed orange juice Sullivan calls the “closest to the real thing.”

GROWERS FIND NICHE

If oranges have a future in Brevard, it will be in the hands of hobby farmers such as Jerry Hunt, a retired general contractor turned grower. Of the 19 Merritt Island acres he farms, six are planted with oranges at 100 trees per acre. Six hundred trees represent a miniscule number for a commercial grower, but every fall, Hunt’s trees produce enough navels to keep his little fruit-stand-on-wheels well stocked. A small sign announcing fruit for sale directs customers to the stand in front of his farm, a business he operates under the honor system.

The secret to growing citrus these days is simple but labor-intensive, Hunt said.

“You have to fertilize them a lot, and that might not be cost-effective for the large growers,” he said.

Hunt sells oranges and other fruit from a cart in front of his Merritt Island grove. JASON HOOK

He leans on KPhite, a fungicide he mixes in with the fertilizer to stimulate root growth and combat the greening that chokes orange trees.

Among the oranges are 27 pomelo trees, a type of grapefruit perfect for eating, but not so great as juice. The trees are experimental varieties provided by the University of Florida. If oranges have had it bad in the last few decades, grapefruits experienced it worse and help is needed to bring the groves back to health.

Despite all the setbacks, farmers like Hunt remain optimistic. Each new year could bring welcome news for the groves.

“It’d still an uphill battle, but this year is looking good,” said the optimistic Hunt.

The end result is well worth the effort. As Sullivan notes on his mail order website, “there is no better way to start your morning routine than with a glass of cold, fresh squeezed orange juice.”

Maria Sonnenberg

Maria is a prolific writer and proofer for Space Coast Living and an adjunct professor at Florida Institute of Technology’s Nathan M. Bisk College of Business. When not writing, teaching or traveling, she can be found waging a one-woman war against her lawn and futilely attempting to maintain order among the chaos of a pack of extremely clueless wirehair dachshunds and an angst-driven basset hound.