Calculating career went from secretary to working on the space shuttle

In 1966, women couldn’t get a credit card without their husbands as a cosigner. They weren’t allowed to run the Boston Marathon, and it wasn’t until 1973 that all 50 states allowed women to serve on a jury. But in that year, Jean Hopkins was working on calculating the expectation of casualty on forced reentry for an experimental space program.

Her career as a pioneering woman in the space industry spanned 30 years and took her from a secretarial position to working with the team who returned the space shuttle program to flight after the Challenger tragedy.

Jean Hopkins was born and raised in the Cocoa area and had a 30-year career in the space industry spanning a period of legendary firsts in space exploration. ANTHONY INSWASTY

Career opportunities came to her in the new and burgeoning space industry because of her math capabilities. She initially worked at Georgia Tech’s Engineering Experiment Station, a research lab supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation. They were utilizing a new technology, a UNIVAC computer, and Hopkins had a secretarial job working for William Atchison, the head of the lab.

“Dr. Atchison had worked on some of the first computers,” she says. “It took up an entire room. It was full of tubes, and we had to program it in machine language.”

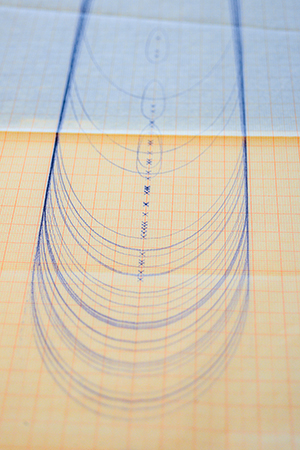

A flow diagram that calculated the expectation of casualty for the space shuttle is among the memorabilia that Hopkins saved in neatly organized scrapbooks.

She eventually learned computer language to program the UNIVAC after Atchison discovered she could type his equations correctly.

“He always promised me that when he had an opening for a new programmer, I would get the job,” she explains. “I always worked for nice people, I’m so lucky.”

SMALL-TOWN GIRL

Hopkins grew up in the Cocoa area but was born in Orlando because the closest hospital in 1934 was Orange Memorial.

Her parents lived in Sharpes, six miles north of Cocoa, which she describes as a very small town. They were Connecticut Yankees who moved to Florida because of her father’s health. They opened a small general store and Hopkins attended school in Cocoa.

“There were 49 students in my graduating class,” she remembers.

Hopkins excelled academically, particularly in math, but that still wasn’t enough to assure her a higher education.

“My father thought, ‘what good is a college education,’ ” she says. “But my mother, who was a nurse, said that because I was a good student I should go to college.”

With a small-town upbringing, her parents were reluctant to send her away to a big university. So, a Presbyterian school, Maryville College in Maryville, Tennessee, was the solution. After her sophomore year she transferred to Florida State University, which was still an all-girls college that would not become coeducational until after World War II. She graduated with a degree in mathematics in 1949.

She met Dean Risher, married him in 1952 and they moved to Atlanta when Risher was hired as an engineer at Georgia Tech, which was how Hopkins ended up working at the computer lab. But she was homesick and the couple returned to Sharpes to be closer to her family and live in the house where she grew up.

EARLY SPACE RACE DAYS

The new world of space exploration was evident all around them in Cocoa. She got a job, again as a secretary, at TRW Systems, an aerospace NASA contractor, and moved up from there. The Space Race was on. The Kennedy Space Center had opened the previous year and Hopkins began her 30-year, full-time, problem-solving career as her work evolved from missiles to rockets and then to the space shuttle.

Today her extensive catalog of binders and folders, chronicles of primary source documents, are evidence of the meticulous approach she adhered to throughout her career.

“I kept them in case I needed to refer back to any of the programs we were working on,” Hopkins explains.

Hopkins, 90, examines one of the diagrams she has kept, reflecting on her career and contributions to space flight safety.

There are flow charts, handwritten notes of long-division equations, as well as letters, accolades, and remembrances from an era in American space exploration, both troublesome and triumphant.

Her work, all with NASA contractors, involved calculations for safety protocols and projections that were, in the early years, placed onto IBM punch cards.

In 1977, while with Computer Sciences Corp., she and her colleagues began work on the microwave scanning beam landing system, a contract that was later transferred to Lockheed.

“We just changed our badges and continued the same work,” she says.

HONORED FOR SHUTTLE WORK

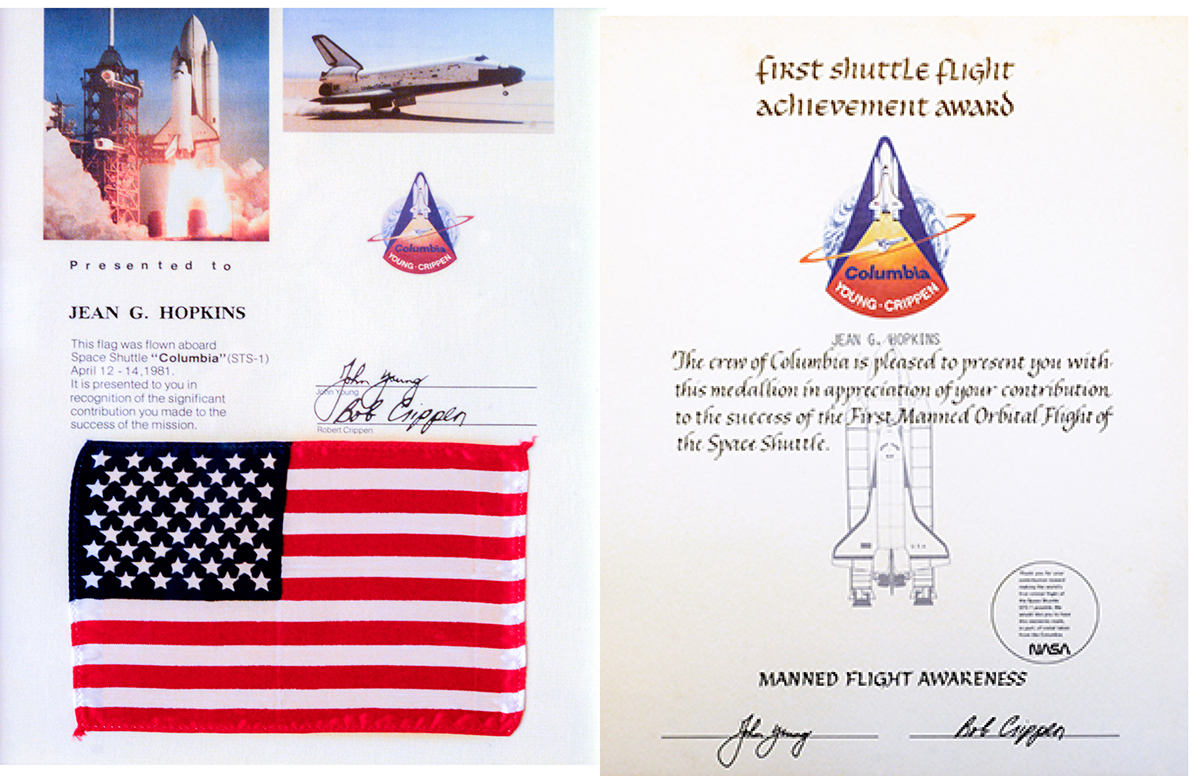

In 1981, space shuttle Columbia, piloted by Robert Crippen and John Young, was the first reusable spacecraft with a crew. Among Hopkins’ memorabilia is a First Shuttle Flight Achievement Award signed by the astronauts and accompanied by a representative medallion.

Left: Space shuttle Columbia, the first crewed shuttle flight, was a monumental achievement for NASA, and Jean Hopkins was acknowledged for her contribution by a medallion and certificate signed by the shuttle pilots.

Right: An American flag that flew aboard the Columbia space shuttle is a prized gift from the shuttle pilots given in recognition of her service to the mission. It is framed and hanging in the office in her Vero Beach home.

The MSBLS was transferred to a PDP-11 computer. The system provided precise elevation, directional and distance data that guided the space shuttle for the last two minutes of flight until it touched down. The PDP-11 was an early, smaller computer that could be taken to various MSBLS test sites, such as California, Africa and White Sands, New Mexico. Hopkins was sent to White Sands and Edwards AFB in California to support the tests.

“They would track a test airplane to certify that the system worked properly,” she says.

Her second husband, John Hopkins, also worked at the Kennedy Space Center as a computer programmer.

“He was an excellent mathematician,” she says. “And I’d get help from him especially when it came to interface it with the computer. And since we drove back and forth to work together, we could collaborate.”

Her daughter, Valerie Risher, remembers them working together on the weekends.

“There were lined yellow pads with pages and pages of long-division calculations on the dining room table,” she remembers.

But there was nothing tedious about the task.

“Math was like a puzzle to my mom,” Risher says. “It was a challenge and fun, something she enjoyed doing.”

By Monday morning, they’d have the problem solved.

Hopkins’ work sites included several locations at the KSC.

“I worked at something called the tin shack for a while.”

It was a building on the runway that previously housed the firefighting teams. In those days, the number of women programmers was growing.

“The firefighters had moved out, so our programming group moved in,” Hopkins recalls. “They had a nice big bathroom for the men and a little one for the women. So, since there were more ladies working there than men, somebody changed the signs on the bathrooms. The secretary put a bunch of flowers in the urinal.”

FRONT ROW SEATS

By 1983 she and her colleagues moved to the blockhouse, a windowless, brick building on the runway of the Shuttle Landing Facility.

As the space shuttle became operational, with multiple flights a year, Hopkins and her colleagues began a routine.

“Every launch we all would leave our desks and offices and we’d go out to watch.”

On a cold January morning in 1986, standing outside with her co-workers, she watched as the space shuttle Challenger briefly gained the sky and then exploded. Remembering the moment, even 35 years later, she pauses and with a catch in her voice, describes the atmosphere with one word — gloom. Her tears are contained but the memory stokes a hard reality of how those working on the project took the defeat personally.

On Jan. 28, 1986, Hopkins was among employees and spectators who witnessed the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger and the loss of her seven-member crew soon after launch.

Two and a half years later, in September 1988, space shuttle Discovery returned to space. One of Hopkins’ scrapbooks contains a letter written on the eve of the launch by Doug Sargen, Lockheed president, to all members of the Shuttle Processing Contractor Team.

“The outstanding accomplishments of these past few months are a tribute to the hard work, professionalism and dedication of every team member. You can all take pride in the undeniable fact that you have indeed been ‘keeping America first in space.’ ”

Space shuttles were ferried to the Kennedy Space Center on the back of a 747. Hopkins remembers that sometimes the 747 would make a circular pass over Brevard County before landing. NASA

STRONG SUPPORT SYSTEM

By 1992 she was team leader for the MSBLS calibration team, a group of five specialists establishing an on-going safe landing system for the space shuttle.

“I always had someone I could go to for help,” she says. “The support system was strong, we always helped each other. It was a great work environment. The only disruptive people we had on our team my boss eliminated or dropped.”

Proximity to the runway offered another interesting perk. When the shuttle landed in California or Texas, it returned to KSC on top of a 747. Hopkins remembers that sometimes the 747 would make a circular pass over Brevard County before landing, just to show that the shuttle was coming home.

“We had this mate-demate device out by the airport,” Hopkins says. “And it would lift the shuttle off the big airplane, move the airplane out and set the shuttle down.”

The dismount process would uncouple the shuttle from the top of the 747, which was then towed or pushed away. The shuttle was suspended in air attached to braces, like a colossal arcade toy grabber machine secured to a set of massive cranes. The landing gear was gracefully deployed and the reusable craft was gently placed on the tarmac.

“All I had to do was walk outside to watch the operation,” Hopkins says.

At 90, Hopkins, who lives in Vero Beach, looks back and confesses to have loved all 30 years of her career. The contributions she made to a critical state-of-the-art endeavor in a time of great exploration helped the program mature and the personnel stay safe. Assessing the risks was her continual focus. And her success is a testament not only to her intellect but also the dedication to her job.

Today, NASA’s KSC has its first woman director, Janet Petro. And women like Jean Hopkins, over her long career, plowed the ground and made the runway safe for a landing like that.

Mary Ann Koenig

Mary Ann Koenig is a writer and filmmaker who directed, wrote and co-produced the award-winning documentary feature film, A Bond Unbroken. She co-authored the memoir Cold War Navy SEALand is a features contributor for Indian River Magazine as well as Space Coast Living. She holds a BA in history from London Metropolitan University and a master’s degree from Columbia University.