College launch

The launch of an Atlas V rocket lights up the night sky over Florida Tech, an educational institution intrinsically connected with the Space Program.

Florida Tech sprung from an ambitious plan and supposedly 37 cents

Sporting his trademark bowtie and next to his beloved MG, Jerome “Jerry” Keuper stands in front of Crawford Tower, one of the buildings at Florida Tech, the university he helped to build. FLORIDA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY PHOTOS

In January 1958, Explorer I, America’s first satellite, proved to the world that the country was ready for the Space Age.

Four years later, when Kennedy Space Center opened, Keuper would find a large supply of engineers eager to advance their careers by enrolling at the new institution of higher learning.

Back on Earth just miles away from where Explorer I launched, missileman and nuclear physicist Jerry Keuper was busy launching another out-of-this-world endeavor, Brevard Engineering College, now known as Florida Institute of Technology.

In his article for Florida Historical Quarterly, Florida Tech’s Gordon Patterson quotes Keuper and his excitement about the school.

“This college is unique,” Keuper said. “Everyone has a full-time job, most have family responsibilities and this college work is over and above other duties. I think it is the only institute of higher learning operating in this country on a spare-time basis.”

From its onset, the school has looked to the skies for students, faculty and programs.

“Brevard Engineering College was the offspring of America’s space program,” Patterson added.

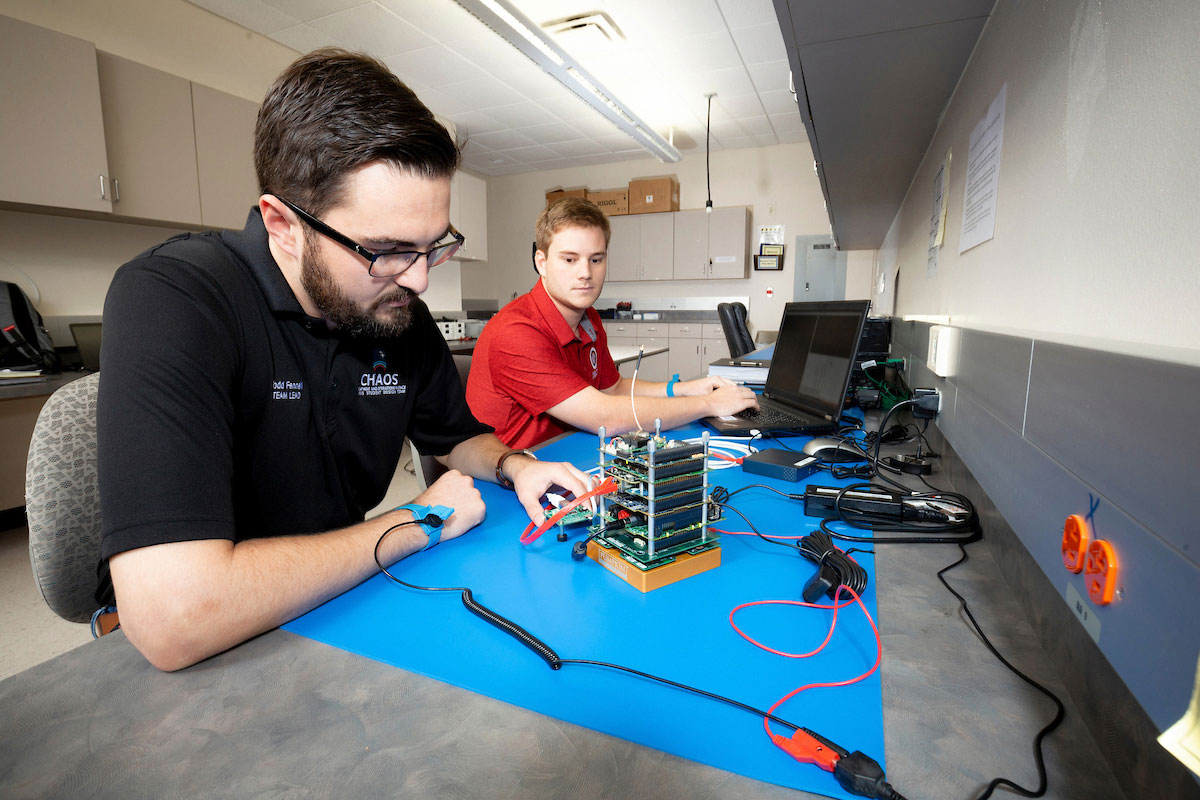

Students assemble a CubeSat, a type of miniaturized satellite for space research, at a Florida Tech lab.

Cutting-edge flight simulators at Florida Tech’s Center for Aeronautics and Innovation are a critical part of training and education programs.

“It was aimed at techs who wanted to become engineers and engineers who wanted to move up the ladder. These people saw education as the way to get ahead.”

During the frantic time of the country’s first foray into space, educational opportunities for the stream of scientists and engineers pouring onto the Space Coast were slim and Keuper sought to fill that void.

The story goes that while shooting the breeze at the old Pelican Inn on A1A in Indian Harbour Beach, Keuper told his bar buddies about his plan to create an educational institution for the engineers enticed to the area with the prospect of swamp pay.

A friend supposedly slapped the 37 cents in his pocket on the bar, saying “here’s your first donation, Jerry. Now, go build that college.”

With those 37 cents, and two-thirds of the PhDs in the area working under him at the cape, plus three classrooms he cajoled at what is now West Shore Junior/Senior High School, Keuper did just that.

“He had 146 students, and everyone worked at the Missile Test Project,” Patterson said.

With plenty of vision and perseverance Keuper launched the precursor to Florida Institute of Technology.

Before 1964, when traditional college-age students began appearing, the school catered to an older, working crowd, with an average age of 31.

Just a couple of years after the school’s first classes, Keuper quit his well-paying job as a senior engineer with the Missile Test Project to devote himself full time to the rapidly growing school. It was a giant leap of faith.

Funding the fledgling college required inventiveness, but Brevard heartily endorsed its value.

“Brevard Engineering College will help us keep engineers in the area,” engineer John Wright told the Orlando Sentinel in 1958.

Wright, who led a dozen engineers at the cape, had enrolled in BEC to earn a degree in space technology.

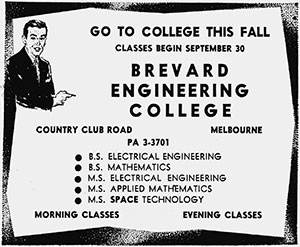

Early ads for the school touted evening classes for working students.

Irving Wolff, head of RCA’s Princeton Labs, visited BEC and was delighted with what he saw.

“Brevard Engineering College is contributing significantly to the added education of the engineers and scientists at the Atlantic Missile Range,” Wolff told the Orlando Evening Star and presented Keuper with a $2,400 donation from RCA, big bucks for the little school.

Two other space cowboys, George Shaw and Homer Denius, helped out. The pair, who founded L3Harris precursor Radiation, also served as directors of the National Bank of Melbourne. After Brevard County schools evicted BEC, Shaw and Denius orchestrated the college’s move to an old bank building on Waverly Place in Melbourne.

Keuper died in 2002, but his successors have continued the trajectory he took that day back in 1958.

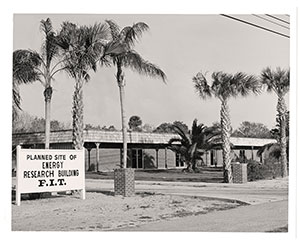

Florida Tech’s sprawling campus grew from a couple of modest buildings.

“Jerry Keuper knew firsthand the excellence, innovation and hard work that were required to build the nation’s space program and we are fortunate he brought that mindset to establishing Florida Tech,” said Marco Carvalho, executive vice president and provost and the school’s acting president.

“He ensured Florida Tech would always reflect the spirit of the Space Age by developing a university that rewarded curiosity and empowered exploration.”

Florida Tech’s connections with the space program continue through a wide variety of research. For example, university researchers have studied Mars mission architectures built on cycle orbits originally pioneered by former astronaut Buzz Aldrin.

The process involves a cycler spacecraft that would stay in an elliptical orbit around the sun, performing regular fly-bys of Earth and Mars. A crew transfer vehicle would lift off from Earth during one of those fly-bys, catch up with the cycler to deliver the crew, and ultimately transport the crew from the cycler to a low Mars orbit.

After the crew finishes its Mars mission, the crew transfer vehicle and cycler will then be used in reverse order to get the crew back to Earth and pick up the next expedition.

“Launching such a spacecraft is doable and actually reasonable,” noted aerospace engineering associate professor Markus Wilde, who with fellow professor Brian Kish and grad student Bhumika Patel, studied the design considerations.

Telescopes on the roof and the 0.8-meter Ortega Telescope in the background are features of Florida Tech’s Olin Physical Sciences building on the Melbourne campus.

Vintage photos show the progress at FIT’s campus.

Assistant professor of planetary sciences Jeremy Riousset, through a collaboration with University of Oregon experimental development researchers Josef Dufek and Joshua Mendes-Harper, is examining lightning on Mars and its potential role in being a catalyst for life on the planet.

The five-year endeavor will involve studying the physics and observability of electrical discharges in atmospheric conditions representative of Earth and Mars, with a goal of furthering understanding of the physics of electrical discharge in diverse environments.

“Is there or has there been lightning on Mars? That is the question,” Riousset said. “Lightning can destroy life, as we know; a lightning strike can cause damage. Lightning can also be a trigger for life.”

An F.I.T. Aviation student works with an instructor on one of the university’s aircraft.

Planes are lined up at F.I.T. Aviation, which is a wholly owned subsidiary of Florida Tech. It is home to university aviation operations, including ground school, flight instruction and air traffic control.

Riousset is also looking to involve the local community through disseminating academic research outside academia via Astronomy on Tap public talks and creating a summer camp using LEGO Mindstorms to introduce middle-schoolers to programing and space science.

Florida Tech was among one of nine original Center of Excellence for Commercial Space Transportation core universities, participating in more than a dozen projects that include air and space traffic control considerations for commercial space; human factors in spacecraft design; and measuring thunderstorm electrical parameters to help reduce incidents of weather-related delays and scrubs.

The school even boasts space royalty among its faculty. Florida Tech professor emeritus and retired Capt. Winston Scott was a mission specialist aboard space shuttle Endeavour in 1996 and Columbia in 1997, logging 24 days, 14 hours and 34 minutes in space. His three spacewalks totaled 19 hours and 26 minutes.

Working together with leaders in the space industry, the school will continue that intrinsic connection with the heavens that Keuper formed more than six decades ago.

“Florida Tech is an ideal partner for the agencies and organizations that are ushering in a new era for the industry of space, a time of extensive competition and rapid innovation,” Carvalho said.

“As a research collaborator, we offered unparalleled agility and expertise. Moreover, we strengthen these companies’ workforces by providing a steady stream of the most employable engineering and science graduates in the country.”

Maria Sonnenberg

Maria is a prolific writer and proofer for Space Coast Living and an adjunct professor at Florida Institute of Technology’s Nathan M. Bisk College of Business. When not writing, teaching or traveling, she can be found waging a one-woman war against her lawn and futilely attempting to maintain order among the chaos of a pack of extremely clueless wirehair dachshunds and an angst-driven basset hound.