SEEING RED

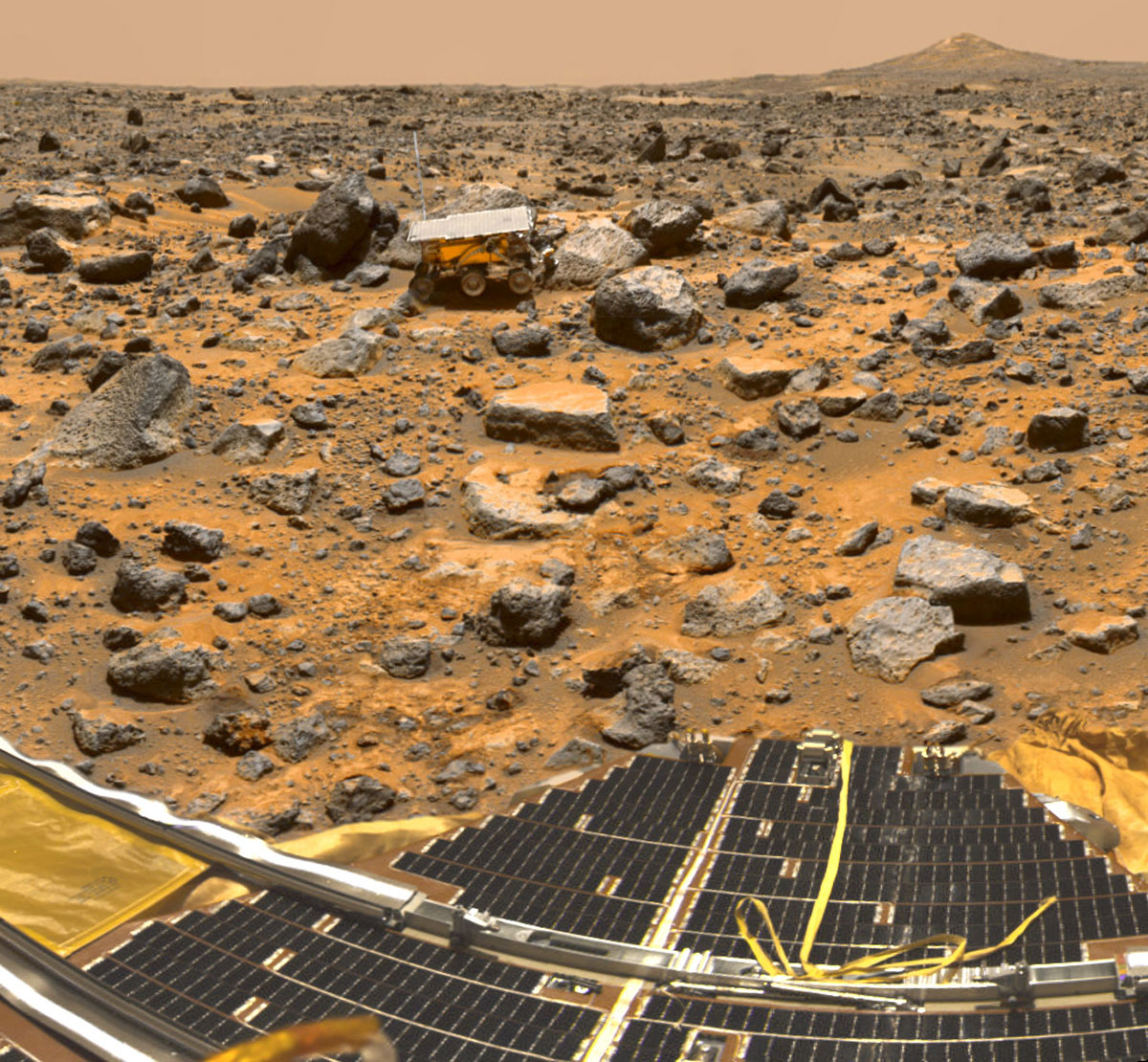

Pathfinder websites had more than 47 million hits the day Pathfinder landed on Mars in 1997. The lander is named the Carl Sagan Memorial Station in honor of the renowned astronomer. The wheeled rover honors civil rights pioneer Sojourner Truth. NASA/JPL-CALTECH

Success of Pathfinder’s mission to Mars paved way for more sophisticated robotic exploration

Veteran radio reporter Pat Duggins, who grew up minutes from Kennedy Space Center, is the award-winning author of two books on space, Final Countdown: NASA and the End of the Space Shuttle Program and Trailblazing Mars: NASA’s Next Giant Leap. PAT DUGGINS

Ten-year-old Pat Duggin had a backyard seat for what he describes as free fireworks from Cape Canaveral. The son of an Air Force chief master sergeant, he has vivid memories of seeing the night sky burst into light with the Pioneer 10 probe heading toward Jupiter aboard an Atlas-Centaur rocket in 1972.

On Jan. 28, 1986, Duggins’ love of space rode with him to the Kennedy Space Center. By then a reporter with WMFE radio in Orlando, he heard colleagues say that the space shuttle Challenger had exploded. With station car keys in hand, he bolted out of the office and drove down Highway 50 toward a mushroom cloud of smoke. The lengthy on-site coverage of the disaster that killed all seven astronauts aboard was the start of the veteran reporter’s career in space news. He has reported on 103 shuttle missions and has interviewed hundreds of NASA astronauts, space workers, scientists, engineers, historians and industry contractors over decades.

To Duggins, NASA’s longtime goal of sending humans to Mars and the many expendable probes it has sent to scout out the red planet merited chronicling in his book, Trailblazing Mars: NASA’S Next Giant Leap, published by the University Press of Florida in 2011. He continues to report on space, now as Alabama Public Radio’s news director and prior to that at NPR.

“Mars is kind of it,” Duggins tells Space Coast Living. “It’s the only planet where humans can go and stand.”

A full-scale model of Mars rovers, displayed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, shows the increase in size from the Sojourner rover of the 1997 Pathfinder mission; to the exploration rover twins, Spirit and Opportunity; to the 2012 Mars Science Lab rover, Curiosity. NASA/JPL-CALTECH

FIRST WHEELED ROVER

The first modern boost to the quest that started with the Mariner 4 probe in 1964 was Pathfinder’s landing on Mars on July 4, 1997. Its success led to larger and more sophisticated landers and rovers up to Perseverance in 2020.

With Pathfinder and the Sojourner rover attached to it, the dream of looking for extraterrestrial life reawakened after the 20-year gap left in the wake of the Viking 1 and Viking 2 landers and orbiters. They transmitted a lot of data for years, not merely months as planned. But the cost exceeded $1 billion. In comparison, Pathfinder cost $265 million including launch and operations, according to NASA.

Omar Baez, a former launch director, recalls his experiences in leading 41 launch missions and being part of 300 countdowns in his more than three decades of work at the Kennedy Space Center. NASA

“The notion that NASA was getting back into the fight, it was really exciting,” Duggins says of the public’s response, including the Mattel toymaker’s Hot Wheels version of the new lander and rover. “They had to scale back on Pathfinder. They had to find a smarter, cheaper and faster way to get the mission done. It worked and they got there.”

Former Launch Director Omar Baez retired in March after a 33-year career at Kennedy Space Center. He was thrilled when Pathfinder and the Sojourner rover set off for Mars aboard a Delta II rocket. “Sojourner was like a toy the size of a large remote vehicle,” Baez says of the first wheeled rover to explore Mars. Pathfinder settled on top of huge beachball-type airbags atop rocky Martian plains known as Ares Vallis. “The mission was highly successful. It paved the way for Spirit and Opportunity.”

Pathfinder outlasted expectations. The rover Sojourner transmitted images and collected chemical and atmospheric data for nearly three months. Its last transmission was on Sept. 27, 1997. Together, the pair showed that landing a robotic wheeled vehicle could work.

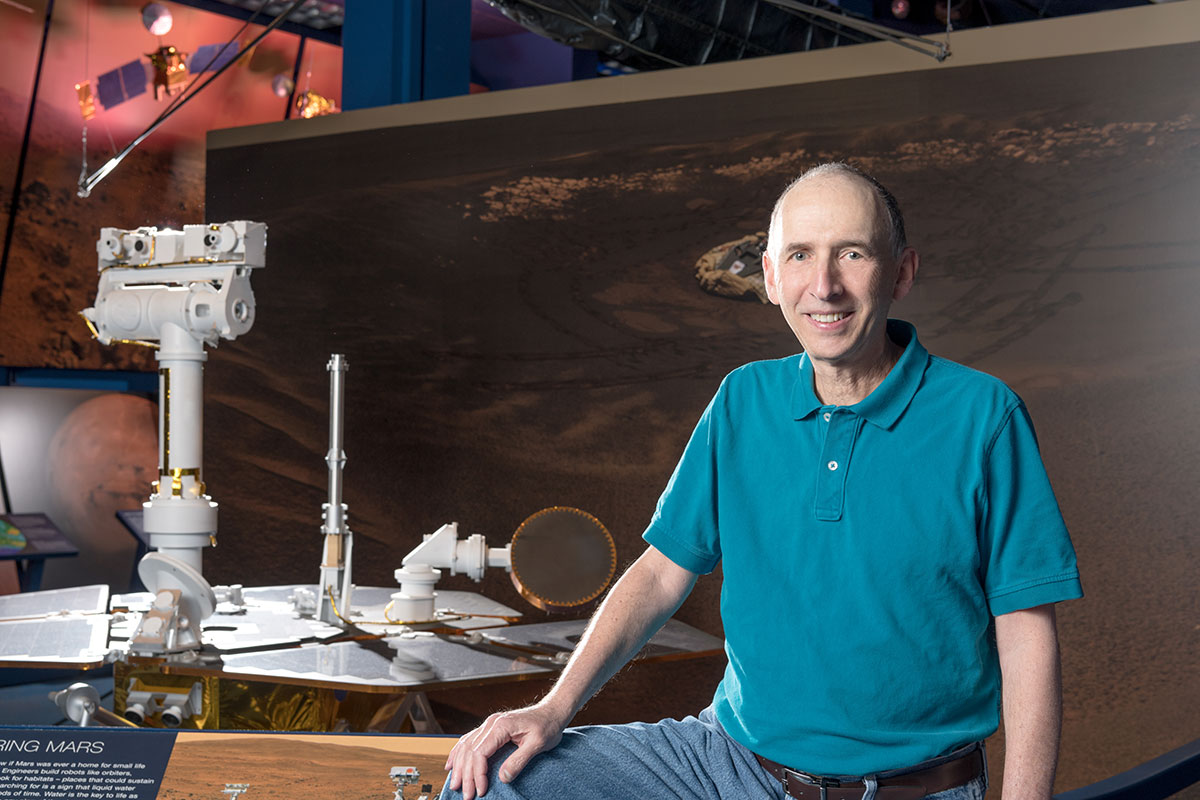

A good deal of Pathfinder’s success is due to the camera design that Dan Britt, now a professor of planetary science at the University of Central Florida, managed. He and Peter Smith teamed up on the project at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology where they worked in the 1990s.

“Part of what we learned with Pathfinder is that literally a picture is worth a thousand words,” Britt says. “That’s really a fast way to learn about alien environments and sight is the best way.”

Pathfinder’s goals were simpler and it was much more limited in its scope of operation than Viking’s mission. “It was by design that it was less expensive,” Britt says. “We had advanced a lot more technology so it was cheaper, and we had learned a lot from Viking.”

Matt Golombek, a chief scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, has led the landing site selections for all 12 Mars missions over two decades, including Pathfinder.

Among their chief discoveries, Pathfinder and Sojourner confirmed a wetter and warmer planet, which the Viking probes had indicated. The public’s enthusiasm at being present for these discoveries and more is memorable to Golombek. People were able to see on computers the first images transmitted from the storied planet 140 million miles away back to Earth after landing.

“After Pathfinder landed, it was the largest internet activity in the world,” Golombek says of that Fourth of July weekend. The World Wide Web was just coming into popular use then, but a lot of people had yet to own personal computers, he notes. “On Monday, people got back to work and could see their computers. It was the first mission data streamed to the internet.”

“It’s been an exciting period during the last 20 years,” he says “I’ve been quite fortunate to be included.”

The success of the robotic rovers came with much trial and error. Launches to Mars can take place only every 26 months, and NASA officials estimated in the early 2000s that about 10,000 successful communications and technical actions are required for a spacecraft to make it from Earth to Mars. Seven landings since Pathfinder and including it succeeded. The rovers grew in size and many infrastructure orbiters and satellites such as the Maven weather satellite and the MGS telecommunication satellite to Mars enhance exploration of the planet.

University of Central Florida Professor Dan Britt’s leadership in managing the Pathfinder camera marked the start of nearly three decades of work in space exploration and in planetary science research. UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL FLORIDA

CELEBRITY TWINS

Golombek at the Jet Propulsion Lab and Baez at the Kennedy Space Center were heavily involved with the twin mission of Spirit and Opportunity in 2003. Excitement for going to Mars had been ramped up for a while in part because, in August 1996, scientists discovered a single-cell life fossil from a Mars meteorite that had fallen to Earth. What Pathfinder indicated in terms of liquid water being on Mars, Spirit and Opportunity confirmed.

“Mars and the Earth first became inhabited by single cell organisms,” Golombek explains of the search for ancient life on Mars. “All of life is related, and all of it has liquid water.”

The golf-cart sized, solar-powered rovers launched successfully in the hot summer despite extreme challenges, not the least of which was a one-second launch window for each rover. An even greater problem was the cork insulation on the rocket.

“Spirit and Opportunity were very special to me,” Baez says. He had just been chosen to lead the office of expendable launches, a five-year stint early in his career at the space center. “We had to launch the mission about a month apart from each rover, and we were having trouble with the cork peeling off in sheets. So we had to peel it off and reapply it. And we had afternoon thunderstorms to cope with. It was a very trying time and a very short span between two identical missions on two rockets.

“We did grit our teeth through a lot of it,” Baez says. “But we made it.”

Golombek also remembers the nerve-wracking suspense of the cork repairs, which were finished only days before launch. The California-based scientist made it to the cape the night of Opportunity’s launch, driving straight from the Orlando International Airport. The twin rovers are highlights of the senior research scientist’s more than three decades of Mars landing site selections.

“Opportunity was the first rover to study rocks on the ground that showed there was water on the surface,” Golombek says. “And plans for the rovers were long-laid enough for people to follow their actions and their travails. Spirit and Opportunity created a following of people.”

Martian enthusiasts followed the rovers’ movements online and also Golombek’s and other scientists’ expert commentary on the TV news outlet C-SPAN.

“We started getting letters and emails from people saying, ‘You should have gone this way,’” he says.

Matt Golombek, senior research scientist and a geophysicist, leads site selections for Mars landers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab. He is part of the team working on return samples of Mars rocks, tentatively set for 2030. NASA/JPL-CALTECH

The twins captivated the world by outlasting their original 90-day mission by years. They landed on opposite sides of Mars in January 2004. Both rovers had a robotic arm, a drilling tool, three spectrometers and four pairs of cameras that provided them a human-like view of the terrain. Spirit traveled 4.8 miles over its six years of operation, while Opportunity traversed 28 miles during its 14-year contribution to science. Perhaps its most well-known discovery related to water that could support life existed in the Endeavor crater, where it detected gypsum, a mineral abundant on Earth.

First labeled lackluster MER-A and MER-B for Mars Exploration Rovers, the twins were later named Spirit and Opportunity from then 9-year-old Sofi Collis’ winning essay contest entry. Opportunity eventually was bestowed a moniker, Oppy, by dedicated jet propulsion lab scientists. In 2009, the twins were inducted into Carnegie Mellon’s Robot Hall of Fame. The 2022 Amblin Entertainment documentary, Good Night, Oppy, won the Critic’s Choice top award for its presentation of the rover and its impact.

“For the people who operate the rovers, we’re Martians,” Golombek says, noting that he often refers to himself as the oldest Martian. “When we’re operating, we’re there. Our collective brains are on Mars, and we refer to the rovers as team members. Humanity is already on Mars. It’s the only other planet entirely inhabited by robots, and those robots are built by humans.”

NASA administrator Sean O’Keefe congratulated 9-year-old Sofi Collis for her selection of the names Spirit and Opportunity for the twin rovers launched in 2003. Her winning essay on the names she chose was among more than 10,000 student entries. NASA

The Delta II Heavy rocket manufactured by United Launch Alliance, on launch complex 17-B at then-Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, was in place to carry the rover Opportunity to Mars on its July 2003 launch. NASA

TO THE FUTURE

The answer to whether humans are alone in the universe is being pursued by Perseverance and the helicopter, Integrity, which landed on Mars in February 2022 despite challenges of the pandemic. Perseverance is collecting soil samples and 10 of them had been deployed in a cache as of March, Golombek explains. NASA plans to send a return lander and two helicopters in 2030 to return samples to Earth.

The infrastructure of satellites orbiting Mars that launched from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and Vandenberg Space Force Base primarily has been and will continue to be essential to exploration on the red planet. “There are all kinds of things we’ve launched into the Mars orbital surface that have exposed the world to Mars,” Baez says.

The launch services team works 20 to 30 missions at a time and from five to 10 years out with about 480 workers in various capacities. Those launches include spacecraft headed for planets within the solar system and beyond, like Pioneer 10’s mission to Jupiter and on to deep space 50 years ago.

“It’s people working together, and we’re bringing in a new generation,” says Baez, the son of Cuban immigrants, reflecting on his career shortly before he retired. “We don’t build the rockets, but we try to do our very best at launching them.”

An artist’s concept of the Spirit and Opportunity rovers shows the robotic arm that allowed each rover to grind into the hard Martian rock. NASA

For the mission to send humans to Mars, it’s also about teams. Rovers alone have difficulty navigating the craggy Martian terrain, and humans would need bubble-like enclosures to avoid radiation and other atmospheric conditions inhospitable to humans.

“Sometime we’ll have to send humans, and it’s always going to be robots and humans working together,” Duggins says. “What the scientists often tell me is that a NASA astronaut standing on the surface can do more in 15 minutes than a robot can do in years.”

Space scientists agree that exploring planets and deep space are essential for resources and long-term survival on Earth. Basic human nature figures in also.

“It’s kind of like, what’s over the horizon,” Duggins says, reflecting on Christopher Columbus’ exploration of unknown lands by sea. “You never know what you’re going to discover.”