In 2016, voters passed a special half-cent sales tax to fund the cleanup of the Indian River Lagoon, the precious waterway that joins the Mosquito, Banana River and Indian River Lagoons through 156 miles of Atlantic Coast waterways that is home to more than 4,300 species of flora and fauna.

So far, that tax has generated $176 million for cleanup projects, with more than $400 million expected over the life of the tax. Because that money is used together with matching grants, the effective cash flow into the lagoon is estimated to be close to $1 billion dollars over the life of the program.

So where are our tax dollars going?

Lagoon Projects

The Brevard County Natural Resources Management Department is responsible for coordinating the work, reporting nearly 40 completed projects, with dozens more underway or about to launch, including:

SEPTIC HOOKUP:

There are 53,178 septic systems in the lagoon basin, and 5,584 of them have been identified as major problems, contributing 31% of the total nitrogen overload to the lagoon, the largest single source of nitrogen pollution. So far only 255 septic systems have been converted to sewer lines. For the most part, hookups to sewer lines are being done at little or no cost to the property owners.

STORMWATER:

Another significant source of pollutants is stormwater runoff. Nothing is going to stop the runoff during major rain events, but work is being done to better control it. Six baffle boxes have been installed around the lagoon so far. The runoff is diverted through the baffle boxes, which remove debris and nutrients that would otherwise end up in the lagoon.

MUCK REMOVAL:

Over time, as much as six feet of black muck, a result of excess pollution, has accumulated at the bottom of the lagoon. Muck releases nitrates into the water, causing algae blooms and fish kills. To date, four muck dredging projects have been completed and two more started. In areas where the muck has been removed, rapid improvement in water quality has occurred.

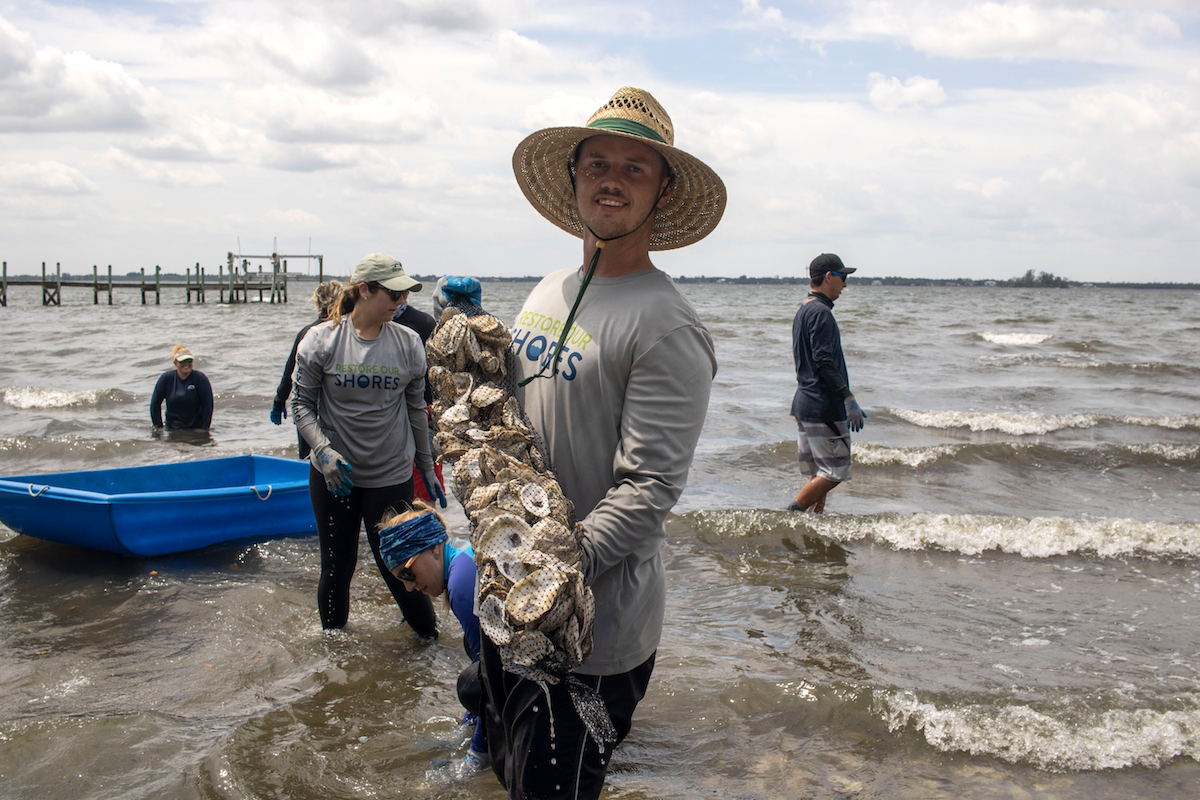

OYSTERS AND CLAMS:

Administered by the Brevard Zoo Restore Our Shores program, more than four million oysters have been deposited in the lagoon to help with filtration. A single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day. It is esti- mated that every single oyster in the lagoon can filter up to 50 gallons of water daily. The 10-year goal is to create 20 miles of new oyster reefs. So far, about two miles have been restored. Super clams, which filter water the same way but at a smaller scale, also are being added to the lagoon cleanup efforts.

Lagoon Future

Virginia Barker, director of the Natural Resources Management Department, remains optimistic about the future of the lagoon. “We are in our stride now and well positioned to implement projects and demonstrate performance and cost effectiveness for the life of the tax.”

There is some concern, however, that the county program may not be robust enough.

One of the strongest indicators of lagoon wellness is sea-grass health. There are seven varieties of seagrass in the lagoon, and according to Leesa Souto, who leads the Marine Resources Council in Palm Bay, all of them are dying. Sea grasses need light, and algae blooms block sunlight from reaching the bottom on the lagoon.

“We are on the verge of a tipping point… this is a long-term project. It took a long time to get here, and it will take a long time to get out of it,” said said Leesa Souto of the Marine Resources Council.

Policy change and regulation are also being considered.

“We can’t buy our way out of this mess,” says Vince Lamb, president of the Indian River Lagoon Coalition, the leading independent advocacy organization for the lagoon. Since the cleanup started in earnest, he said, “we have had more pollution going into the lagoon than we have cleaned up.” Tougher environmental controls are needed at both the local and state government level, and Lamb believes policy changes is necessary.

Fred Mays

Fred Mays is a freelance writer and photographer who resides in Satellite Beach. He is a retired television journalist, and active on media issues with the Brevard Indian River Lagoon Coalition. His blog is www.floridaunplugged.net.