Cosmic Alliance

Spacelab crew, left to right, Robert Parker, Byron Lichtenberg, Owen Garriott and German physicist Ulf Merbold prepare for Spacelab’s first flight on Nov. 28, 1983. NASA

NASA’s Spacelab program with the European Space Agency charted the course for the International Space Station

Ann Bolton began her demanding career as the spaceport’s first female co-op student in 1962.

ANN BOLTON

A reusable laboratory flown on the space shuttles, Spacelab’s launch from the Kennedy Space Center on Nov. 28, 1983, paved the way for the International Space Station. Spacelab housed scientific experiments in low-Earth orbits, contributed vast scientific research results and created a legacy of international cooperation over its 17 years of flights.

Former space center payload operations planner Ann Bolton, 79, worked on Spacelab in its early phase. Her bachelor’s degree in math from Rollins College’s then-Patrick Air Force Base campus prepared her well for computer systems analysis. Shortly after 1980, she was assigned to a team that traveled to Bremen, Germany, for work on the project. NASA and the European Space Agency had agreed nearly a decade earlier to collaborate on the lab.

“It was before people even knew that Spacelab was coming,” Bolton says in a telephone interview from her Cocoa Beach home. “It was brand new.”

Bolton’s time in Europe was spent planning before the lab being built in Europe was completed and delivered to the Kennedy Space Center. “We were wide-eyed listening to everyone,” Bolton recalls of many meetings in Germany and Holland.

In February 1982, Vice President George H.W. Bush presaged Spacelab’s legacy at the unveiling ceremony of the flight hardware at the Kennedy Space Center when he said, “The knowledge Spacelab will bring back from its many missions will belong to all mankind.”

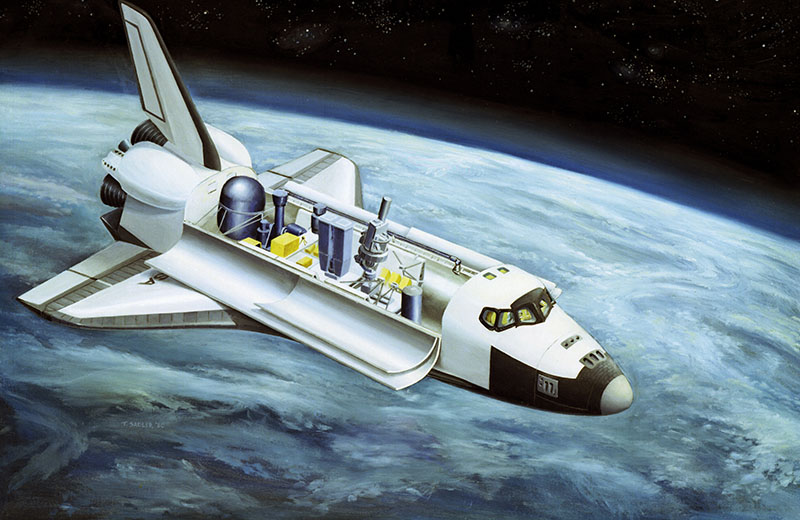

Spacelab-2, housed in the cargo bay of the orbiter so its scientific instruments are exposed directly into space, was launched aboard the shuttle Challenger July 29, 1985.

MANY MISSIONS

Ann Bolton, who retired from NASA after a 30-year career, volunteers at the Cape Canaveral Lighthouse to preserve its legacy. ANN BOLTON

Spacelab flew 36 missions and completed about 800 experiments in materials science, life science, physics and astrophysics on NASA’s space shuttles. The European Space Agency built the lab, the Marshall Space Flight Center managed it and the space center launched Spacelab-1 on the STS-9 mission of space shuttle Columbia on the late November 1983 flight.

At a cost of $1 billion, the entire lab comprised several units. The two main modules were aluminum, pressurized cylinders each the size of a medium trailer where scientists and astronauts worked in regular clothing. Each was housed on separate missions in the space shuttle’s payload bay. The interior of the main module was designed with racks for many experiments in a small space. Spacelab also had U-shaped pallets attached behind the lab module and were exposed to space on the shuttle’s exterior with equipment such as telescopes and antennae.

On its first, 10-day mission, the crew completed more than 70 experiments from 14 nations while the shuttle orbited the Earth 166 times, according to NASA. The massive number of experiments required nonstop work for crews both in space and on the ground.

Bolton was on the NASA payload team that tested “the experiment instrument’s interfaces with racks, with the Spacelab systems and computer, with the shuttle systems and computer, and finally, the downlink,” she explains. “We also tested portions of the mission sequences that were representative of the maximum power consumption, astronaut participation and computer interactions.”

She retired in 1992 after a 30-year career that started as the spaceport’s first female co-op student. She is active in the NASA Alumni League and Cape Canaveral Lighthouse preservation. Her work on Spacelab remains vivid to her in part because of her love of math and physics.

“Working on flight equipment was really exciting for me,” she says.

DEMANDING CAREER

Payload systems engineer Mike Haddad bids farewell to space shuttle Atlantis shortly after its final mission. He began work on Spacelab right after college.

Like Bolton, Mike Haddad enjoyed the demanding career. He dreamed of working at the space center before becoming a full-time payload engineer in 1982. Shortly after he graduated the University of Central Florida with a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering, Haddad was assigned to equip Spacelab’s pallets that held telescopes, antennae and other sensors.

“We were in our early 20s right out of college,” Haddad says. Now retired, the 64-year-old Cocoa Beach resident met the challenge. “There was only one Spacelab on the planet and it cost millions of dollars.”

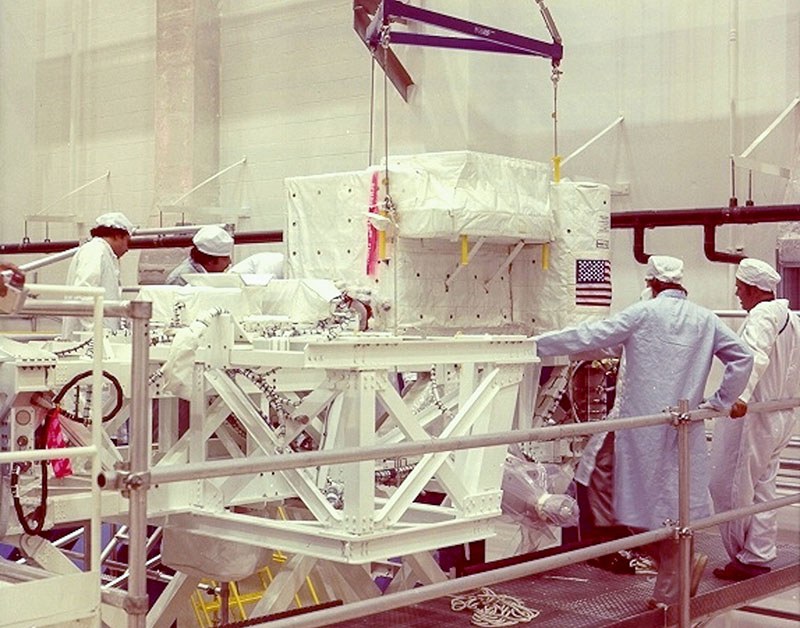

During Spacelab’s pinnacle of missions in the ’80s, the technicians worked 16-hour days, seven days in a row. At one point, Haddad was working four missions simultaneously setting up experiments for astronauts to conduct in space and assembling flight hardware. Setting up a large format camera and the orbital refueling system for the STS-41-G mission in 1984 remains his most memorable

“I reviewed the drawings and put that together with my hands,” Haddad says. “We got to work directly with the parts. I’d write the procedure and then turn the bolts, connect the cables and service the fluids and gases.”

Technicians also assembled many partial Spacelab payloads with a much smaller box-like structure for flights such as the STS-61C on the shuttle Columbia in 1986 that carried pilot Charles Bolden Jr. and payload specialist Bill Nelson, both of whom later became NASA administrators.

Haddad and other engineers at the space center worked closely with the astronauts and with scientists worldwide. Often technicians traveled to the Marshall Space Flight Center to advise astronauts in flight on experiment procedures.

“A lot of what we did was a precursor to the International Space Station,” Haddad says. “It was a precursor to the Hubble and even to the James Webb telescopes.”

Haddad, left, helps install the orbital refueling system in the Kennedy Space Center’s Operations and Checkout Building for a 1984 Spacelab mission. MIKE HADDAD PHOTOS

LESSONS LEARNED

Spacelab gave way to the space station when construction on it started in 1998.

Everything crews learned from Spacelab was applied to the burgeoning, new outpost.

“We crammed everything into the shuttles for Spacelab for experiments to be run for a period of days,” he says. “Now on the space station, experiments run for years.”

Haddad and Bolton agree that Spacelab was critical to the space program.

“The international cooperation for science was the most important thing,” Bolton says. “That is still important today.”

Haddad has preserved Spacelab’s history in a book he and David Shayler wrote, Spacelab Payloads: Prepping Experiments and Hardware for Flight, published in January by Spring Praxis Books. Two years prior to Spacelab’s ending in 2000, Haddad helped load electronic equipment from the experiments onto racks in one of the modules before it was shipped to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

On one weekend in September 1998, Haddad and a few friends gathered to load the module before its eventual display at the Steven Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

“It was our life,” he says. “We wanted to make it look like what we worked on when it was orbiting the Earth.”