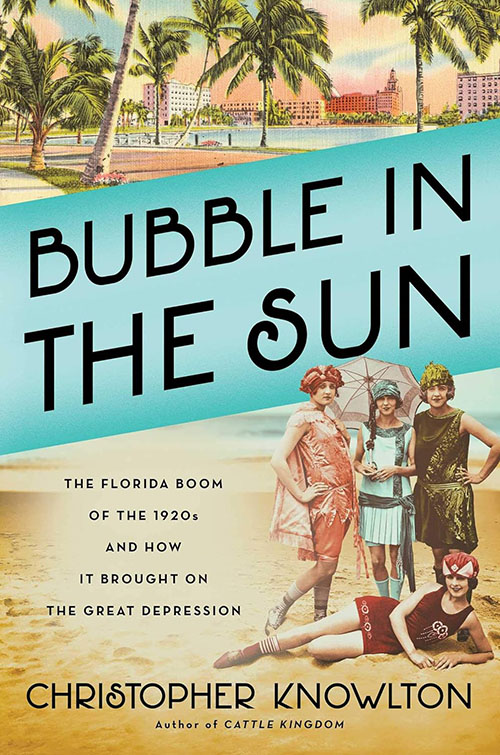

Bubble in the Sun

The Florida Boom of the 1920s and how it brought on the Great Depression

Conventional wisdom regarding the causes of the Great Depression is challenged in this history of South Florida’s excesses during the Roaring Twenties. The Florida land boom, which peaked in 1925 and was followed by the land bust, led to the financial collapse of companies and, subsequently, banks, according to the author.

The saga of South Florida’s boom and bust during the Roaring Twenties gets a fresh take in this look back at an era of frenzied speculation in real estate that was followed abruptly by lost fortunes, shattered dreams and, the author argues, an early start to the nation’s Great Depression.

Drawing on his background in finance as well as journalism, and utilizing an abundance of sources, Christopher Knowlton makes a convincing case that the boom, which peaked in 1925, and the bust, which followed in 1926, had a far greater impact on the national economy than the 1929 stock market crash, favored by conventional wisdom. He shows that many Northern banks failed, at least in part, because millions of dollars of depositors’ money flowed out of their coffers to ill-fated land buys in Florida.

Knowlton writes in highly readable style about colorful characters who shaped South Florida during the era, including Carl Fisher, developer of Miami Beach; George Merrick, planner and builder of the city of Coral Gables; and Addison Mizner, the eccentric architect who walked around Palm Beach with his pet parrot, Johnnie Brown, perched on his shoulder. Mizner’s Mediterranean Revival style is still evident in Palm Beach, Boca Raton and the Treasure Coast community the author was acquainted with as a boy. When he was growing up in the 1950s and ’60s, Knowlton spent 14 consecutive spring breaks in a “pink stucco Mizner-style house in Riomar on the edge of Vero Beach,” in the care of his grandmother, Ruth Bull Rathbone. She took his brothers and him on road trips around Florida. Later, Knowlton and his wife, Pippa, retraced the route of Henry Flagler’s Florida East Coast railroad from St. Augustine to the outskirts of Miami, where they took an airboat tour of the Everglades.

Flagler, former Standard Oil tycoon, with partner John D. Rockefeller, made Florida’s East Coast appealing to wealthy vacationers in the late Gilded Age by building a string of luxury hotels, including The Breakers in Palm Beach. After his death in 1913, the focus changed, and with that came tens of thousands of home buyers eager to buy lots in newly platted subdivisions from Coral Gables to Naples. The Roaring Twenties brought apparent prosperity to people who now had access to home mortgages. Installment credit, formerly used to finance pianos and furniture, now allowed borrowers to buy cars

and refrigerators.

It led to a migration to South Florida that was bigger than the California land rush of the mid-19th century or the Oklahoma boom of 1889. In 1925 alone, 2.5 million newcomers moved to the nation’s newest frontier. Unlike California, sparsely developed South Florida was not a continent removed from population centers in the Northeast. Plus, its winters were warmer than those of California. One participant described the migration of real estate buyers as “the possessive pilgrimage of army ants.” The crowd of visitors, eager to own a piece of the Arch Creek section of Miami Shores one morning in 1925, was so massive that buyers threw their checks at the salesmen, who collected them in barrels. The section sold out in less than three hours, for $33.7 million, which was oversubscribed by $11 million.

Significantly, in 1924, Florida had become the first state to abolish the state income tax and inheritance tax.

“The move was designed to tempt wealthy residents of other states to move their domiciles to Florida,” Knowlton writes. “It worked: Florida went from being an attractive vacation venue to an alluring tax haven overnight.”

The boom started to cool off early in 1926, with land prices dropping and demand easing, but the major developers, their bankers and local politicians seemed to think it was just temporary. A fire that destroyed The Breakers hotel in Palm Beach in 1925 might have served as a cautionary tale, if anyone had been paying attention, the author notes.

One Wall Street speculator who was staying at The Breakers with his family said they lost no more than $20,000 worth of clothes and jewelry in the fire. Another guest who escaped only with the sport coat, white linen knickers and golf hose he was wearing, remarked to a reporter, “Nero fiddled while Rome burned. I played golf while The Breakers burned.”

The hotel was rebuilt and has lasted, but the fire was confirmation that “disaster could strike — often when you least expected it.”

On Sept. 17, 1926, a natural disaster did strike South Florida, a hurricane that arrived in the middle of the night with little warning. The Red Cross calculated the loss of life at 373, including 150 who drowned in Moore Haven, on the western edge of Lake Okeechobee. Property damage in a 30-mile swath of South Florida was estimated at $500 million [$6.9 billion in today’s dollars].

“It would prove to be the most expensive catastrophe in the history of the United States since the earthquake and fire in San Francisco in 1906,” Knowlton writes.

Even though developers were quick to assure the public that things would soon be back to normal, with one claiming that damage was “greatly exaggerated,” the wounded housing market in South Florida was slow to recover. The consequences were far reaching.

“When the single biggest demand for building materials — the Florida housing market — simply went away, leaving construction companies and building materials companies around the country overextended, a downward spiral began,” he said. “Nervous investors pulled back.”

Knowlton tells another cautionary tale, this one about a boom-era project that sounded good at the time but proved to be an environmental disaster: The Tamiami Trail that cut through the southern Everglades to link Tampa

and Miami.

Even Marjory Stoneman Douglas, who later became the best-known champion of the Everglades, supported the road project as a “symbol of economic progress.” Knowlton writes that the road kept water from flowing south and became a “long killing field” for wildlife. Later Douglas, author of the 1947 book about the Everglades, River of Grass, admitted she was wrong about the road, saying “What a liar I turned out to be.”

Knowlton, former London bureau chief for Fortune magazine, has contributed to the New York Times and Wall Street Journal. He is the author of Cattle Kingdom: The Hidden History of the Cowboy West. He was in the investment business for 15 years.

Here, he combines meticulous research with an engaging writing style to describe an era in Florida history that has often been glossed over or forgotten. Readers, even those who are Florida history buffs, will learn plenty.

Janie Gould

Janie Gould (editor and lead writer) is a longtime Indian River Magazine writer and creator and host of the WQCS radio show Floridays. A lifelong resident of Vero Beach, she is past president of the Indian River County Historical Society and a former director of the Florida Historical Society and the Heritage Center of Vero Beach. She has published two illustrated volumes of Florida stories as well as a cookbook.