The Drive

Saturday, February. 3, 2007

Astronaut Lisa Nowak woke up in her Houston home at the end of a cul-de-sac on Parsley Hawthorne Court that Saturday, not intending to launch herself into infamy.

Nowak was alone in the red brick house. Her 14-year-old son and 5-year-old twin girls were spending the weekend with her husband, who had moved out just before Christmas. Her son’s birthday was that coming week.

She looked into the room with her vast collection of stamps for making cards, the stamps with which her girls loved to play. Her crop of 400 African violet cuttings were growing throughout the house, although some were wilting after weeks of neglect. She had propagated them from just eight plants left behind by her friend Dr. Laurel Clark, who had died on board the Space Shuttle Columbia . It was as though, in her mind, the woman’s life somehow continued through these plants.

Lining some of her bookshelves were rows of the crime novels she told reporters she liked to read.

She had been thinking about what she needed to do for herself, envisioning it, planning it, for nearly a month–ever since her boyfriend told her he was seeing someone else.

In mid-January, she had logged in to her work computer on the sixth floor of an office building at Johnson Space Center and went to the MapQuest site to get directions from Houston to Orlando.

She had gone to her local Sports Authority and bought a knife and BB pistol, along with ammunition and a can of pepper spray, paying cash for it all.

That week, at her boyfriend’s apartment and on his USS Nimitz aircraft carrier stationery, she had hastily scribbled his new girlfriend’s flight itinerary, her unlisted home phone number that she had found in his phone bill–the number he called repeatedly. Most importantly, she wrote down

the hour that this woman, Colleen Shipman, would arrive back in Orlando on a United Airlines jet late Sunday night, February 4th.

At home that Saturday morning, Nowak packed her black duffel bag. Like any well-trained NASA employee with an obsessive attention to detail, she had made a list of what she needed: knife, BB pistol, ammunition, hammer, plastic gloves, and a disguise. And cash–a lot of cash to pay for gas and hotels. No need to leave a paper trail of credit card and debit card purchases. She wrote it all down on her astronaut “flight events/history/briefing” stationery.

She got into her husband’s blue BMW, with its fading paint, and left her suburban home, the one with the snapdragons planted around the brick mailbox. She headed to her local grocery store, and, at just about 1:00 p.m., she bought a phone card with 100 minutes, paying $6.50 in cash. She had left her cell phone, with its tracking device, at home.

It was a cool day on the first Saturday in February. She was leaving behind her office on the sixth floor at the famed Johnson Space Center, a place where she had spent 10 years perfecting maneuvers in space shuttle and space station replicas, and in simulated zero gravity, packed into the bulk of a space suit. She worked with a team of people who, like her, were the most elite professionals in the world.

And like her, they had perfect credentials, perfect track records, and perfect personal lives. At least to someone peering into their tiny capsule, that’s how it all seemed.

Her plan was perfect, too. Nothing could go wrong, she thought.

She merged onto I-45 and then onto I-10, to make a turn that would, nearly a thousand miles later, allow the world to watch her tumble from her privileged pedestal.

But for now, her mind was on one thing alone: finding her boyfriend’s new love interest so she could, hopefully, get him back.

Nowak pushed the pedal down, knowing she had a 15-hour drive ahead of her. Soon the plains of Texas gave way to the marshes of Louisiana as the sun dipped below the horizon

behind her. The streetlights flashed one after another overhead through Mississippi, Alabama, and North Florida.

Nowak didn’t want to be noticed on this trip, didn’t want to stop. She didn’t want people to remember seeing her, and she was purposely limiting her contact with anyone. So, rather than utilize rest- stop bathrooms, she would later tell an Orlando Police detective, she pulled to the side of the road, grabbed one of her twin daughters’ diapers from a box she had left behind in the car years earlier, slid it underneath her and relieved herself. In her world, it was normal for astronauts to use diapers–called maximum absorbency garments by NASA–in flight suits and training suits. She put two used diapers in a large trash bag on the floor of the rear seat.

Just after 10:30 p.m. that night, she pulled off the interstate at DeFuniak Springs, a speck on the map between Pensacola and Tallahassee. It was near Eglin Air Force Base, where she and her husband had done survival training while in the Navy. She turned into a Day’s Inn parking lot, grabbed her bags, and checked in under a fake name–Linda Turner–paying a little more than $50 in cash for the stay.

She crawled into the bed in the generic room, number 118, with a polyester, floral spread on the bed and cheap, framed prints on the walls.

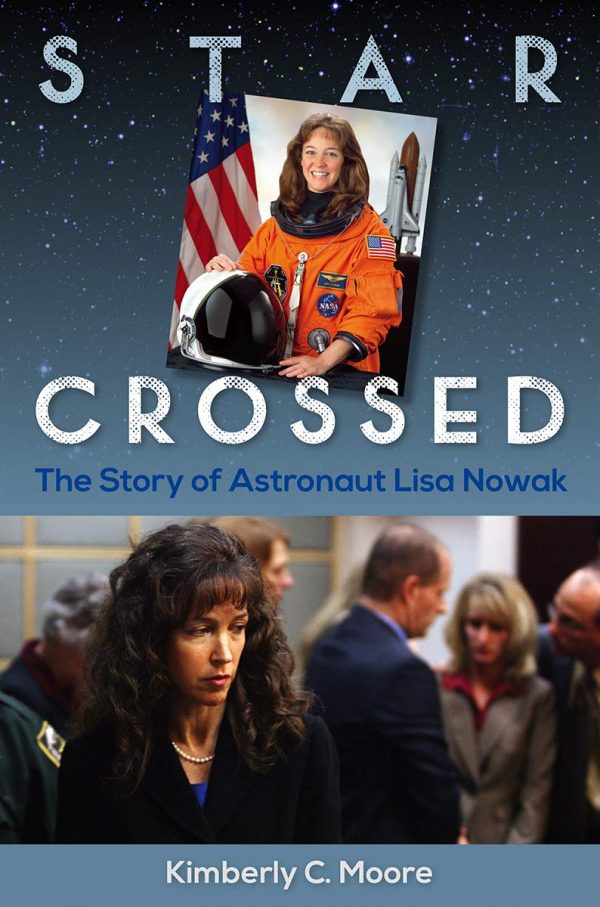

Her Independence Day flight into space had taken place just seven months before. She lifted off on that blistering afternoon from launchpad 39-B at Kennedy Space Center, heading to where only a few hundred others had been before her. All as hundreds of thousands of people watched from the space center, the beaches, and rivers, and on television.

She had worked all her life to reach that pinnacle. Her parents encouraged her and told her she had to be the best, could never misbehave, and must have perfect grades. They expected perfection from their three daughters, and she worked hard to please them. And she expected perfection from herself.

In high school, she watched as Sally Ride was selected as one of the first American women astronauts. She knew that if she studied her hardest and became the best in everything she tried, including excelling in advanced classes, running track playing field hockey and serving on student

government, she might make it, too. All it required was perfection on her part.

Her trajectory to astronaut was a textbook example of creating a plan, following it, and achieving it. She graduated as co-valedictorian of her 1981 class at C. W. Woodward High School in Rockville, Maryland. That achievement, her stellar grades, and her leadership skills propelled her to an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. That’s where she met her husband, whom she married in 1988. A stint at Johnson Space Center before obtaining her master’s degree in 1992 put her on the right track to become the right stuff.

She applied six times and was eventually selected in 1992 as a test pilot in Patuxent River, Maryland, learning to fly more than two dozen high-performing aircraft, even as she became a mother that year.

Finally, in 1996, NASA called her name and gave her a royal- blue astronaut’s jumpsuit. She, her husband, and their young son moved from Patuxent River, Maryland, to Houston, Texas. Her husband became a communications specialist at the command center. And she went through grueling training sessions in conditions that would make the average claustrophobic lose their minds, in a bulky, hot flight suit to simulate zero gravity. She trained for different life-and-death scenarios, again and again. She repeated the same maneuvers over and over, day after day, even after her friends perished on board the sSpace sShuttle Columbia.

Another part of her job was to visit the various space centers around the country, where parts of the shuttle were made, and talk to the workers there. She was away from home quite a bit.

But when she was home, she had the perfect life. Or so it seemed to family, friends, and neighbors. A nearly twenty20-year marriage. A beautiful house in a quiet neighborhood. Two sisters who loved her and parents who loved her and had encouraged her all her life.

Despite fertility problems, Nowak wanted more children after listening to her son pray for siblings each night. She suffered the devastating heartbreak of two miscarriages before giving birth to twin girls in the fall of 2001.

One morning in February 2003, she watched in horror as the Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon re-entering the Earth ’s atmosphere. Her friends, her astronaut classmates, were lost in the early- morning, clear, blue sky. The Space Shuttle Columbia accident brought indescribable grief and pain into her orderly life. This wasn’t supposed to happen.

At the time, her husband, Richard, a fellow U.S. Naval Academy graduate, had been deployed by the Navy for America’s War on Terror. And so it fell to her elementary-school-aged son to comfort her. And in turn she comforted her friend’s son and helped astronaut Laurel Clark’s family deal with the logistics and paperwork that come with the death of a loved one.

Her journey from Texas to Florida was taking place a few days following the fourth anniversary of that horrible day.

She also watched as the U.S. space program sat at the precipice of dying. It was had been up to her and her fellow crewmates to help save the space shuttle program during their July 2006 flight.

Her marriage had been crumbling for years. She and Richard agreed that they would stay married until after her space shuttle flight, but that was delayed because of the accident and safety concerns from 2003 until 2006.

Her star-spangled flight into low -Earth orbit was textbook, NASA perfection. Every detail had been planned, followed, and executed flawlessly by Nowak and her crewmates. When she returned from space, she began making plans with the new man in her life.

Neighbors said they had heard the sounds of dishes breaking in November 2006. A month later and just five months after Nowak went into space, Richard moved out.

She waited for years to tell her parents and sisters that her marriage was falling apart. She hadn’t said a word to them about her new love.

Now her husband was living elsewhere, and the lawyers were handling things.

The façade of her life was peeling apart, and all this perfection, she learned, has a price.

She had turned to a colleague for support. Billy Oefelein was handsome, smart, and understood the demands of the job. At first they were just friends–both were married to other people. Then, beginning in 2004, during and after a survival training mission in the frigid temperatures of Canada, they began spending more and more time together: riding bikes, training for triathlons, working out in the astronaut gym. And she began thinking about him more and more. His wife filed for divorce in 2005.

When she told her mother that her marriage was over, the older woman stopped talking to her. This wasn’t perfection, this wasn’t what they demanded and she had always given to them. It would tarnish the family in the eyes of friends and neighbors on their Rockville, Maryland, street, the one lined with trees that turned golden, amber, and ruby in the fall. And it would sully the family’s name with St. Elizabeth’s Catholic Church. What would everyone think?

She no longer cared what anyone thought. Anyone except Billy. She suspected something was wrong when he hadn’t returned her repeated phone calls after he finished his space shuttle flight in December 2006. Then in early January, he told her: there was someone else, and he was in love with her.

She wished him well and asked if they could still train together for an upcoming bike race. Within days of his news, she hopped on a training flight with him. She clung to hope.

At home, she was sick. She couldn’t eat–her stomach in knots–she had lost twenty20 pounds, with her weight dropping to 107 pounds in the span of about six weeks, making the 5’4 woman look gaunt. She couldn’t concentrate and had been stopped by Houston Police three times. She cried a lot and she couldn’t sleep, her mind churning over and over the facts of her life and how to possibly fix everything.

At work, they had recently told her she would not be chosen for one of the last space shuttle flights. She would probably never fly in space again after some of her colleagues had described her as “uncooperative,” “prickly,” and “not a team player.”

Her marriage had failed, she had failed in her job by not getting another shuttle flight, and now her relationship with the other man was failing.

That’s when she began thinking. And planning.

She hadn’t slept much, if at all, that Saturday night, but checked out of the DeFuniak Springs hotel at 10:45 the next morning and began the final leg of her trip — as Bruce Springstein sang a “broken hero on a last-chance power drive” — to a hotel near the Orlando airport. She would utilize their parking lot, take their free shuttle to the airport, and then lie in wait.