Don't be Scared!

Though sharks can appear quite intimidating, the chances of being the victim of an unprovoked shark encounter are lower than your chances of being struck by lightning, injured in a hunting accident, or even attacked by a domestic dog, according to the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.

FIT scientist proving that sharks are the ones in danger

Toby Daly-Engel and research lab assistant Lila Xenakis share a smile. Xenakis, a marine biology major and member of the Society for Women in Marine Science was nicknamed the ‘White Shark Sponge Queen.’ STEVEN HICKS

As the oceanic spectacle of the annually televised Shark Week approaches, fans around the world are gearing up for thrilling encounters and insightful education on these magnificent predators. While the Discovery Channel’s week of programming in July has become required viewing for a generation of would-be shark scientists, filmmakers and armchair thrill seekers, it’s not just about entertainment.

For Toby Daly-Engel, the director of Florida Institute of Technology’s Shark Conservation Lab, and an associate professor in the College of Engineering Science and Ocean Marine Sciences, it’s an opportunity to raise awareness and appreciation for these captivating and often misunderstood creatures, as well as educate folks about the importance of shark conservation.

Last July, she was featured in an eight-episode National Geographic series, When Sharks Attack and Why, as one of a handful of women in the field.

Her fascination with sharks began as a child. “While I’ve always loved nature and animals, I grew up in upstate New York, so I think my first encounter with a shark was a viewing at an aquarium during a trip to Coney Island,” she recalled. “My mom gave me my first children’s book about sharks. She told me she remembered how curious I was about them.”

Daly-Engel, director of the Florida Institute of Technology Shark Lab, is in her element at sea. The Brevard lab lends itself to easy access to the Indian River Lagoon and Atlantic Ocean for her work outside the lab. FIT

She joined the faculty at Florida Tech in August 2017, where she has mentored undergraduate and graduate students in her lab. She has authored more than 35 manuscripts detailing her work and has been featured on dozens of media interviews and YouTube videos.

“Though many refer to me as a shark biologist, I am actually a molecular ecologist,” Daly-Engel said. Her research integrates molecular techniques with data from field-based samples, in order to study and track the mating, reproduction and habitats of sharks, as well as how climate change impacts them and other migratory marine species.

“We are interested in how reproductive behaviors interact with the environment to influence species, populations, and genomes,” she explained. “Deep sea sharks are all shaped by similar evolutionary pressure, so they end up looking a lot alike. Thus, we rely on DNA to tell us how long this species has been on its own and how different it is.” Interestingly, sharks have some of the slowest reproductive intervals of any animal or fish on earth, and many stay pregnant for up to two years.

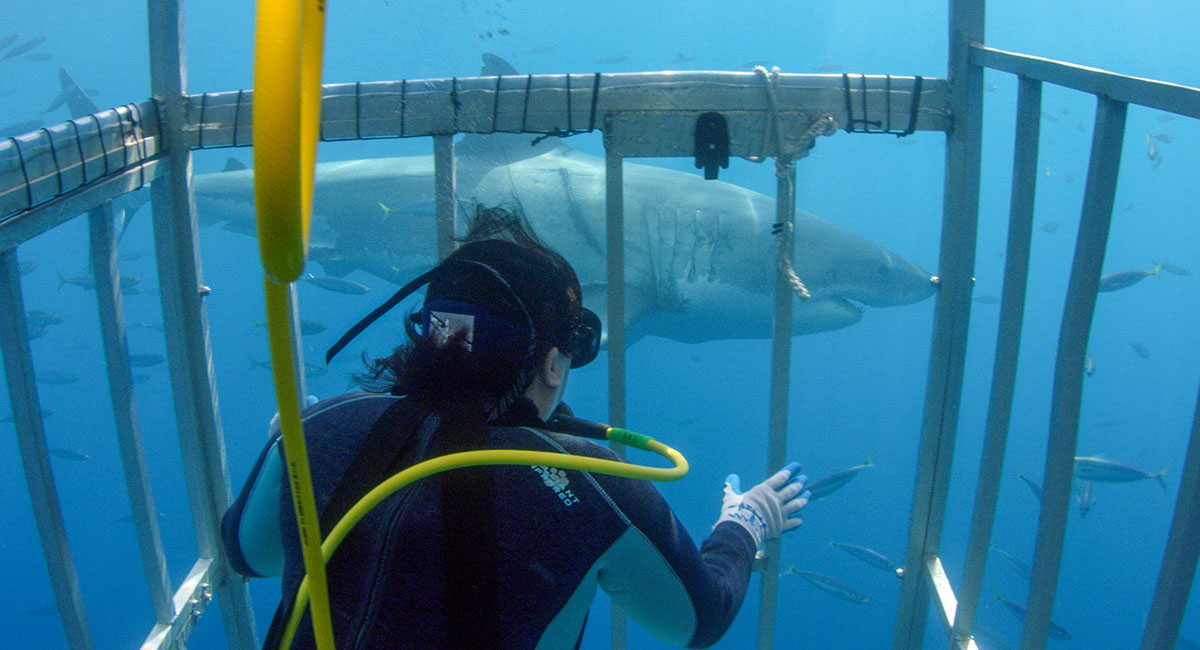

Daly-Engel observes from a submerged protective metal cage that allows an up-close look at many species.

AT RISK

Testing DNA is routine at the lab. Daly-Engel was part of a team that discovered a new shark species, Squalus clarkae, known as the Genie dogfish shark. STEVEN HICKS

The media’s characterization of sharks as vicious threats has a huge effect on public perceptions, including those of lawmakers and fishermen, who have a direct impact on sharks’ conservation. Scientists estimate that overfishing and other manmade disturbances are responsible for the death of more than 100 million sharks globally per year.

“Unfortunately, losing these predators is a first step of eco-system collapse,” Daly-Engel said.

While there are myths that sharks are predators that are looking to attack humans, most shark bites are simply a case of mistaken identity. “Depending on the season, and conditions of the water, it’s likely swimmers or surfers may be no more than 50 yards away from one of the most common species, blacktips, found here on the Atlantic coast of Florida — at any given time,” Daly-Engel said.

According to the University of Florida’s International Shark File, the vast majority of unprovoked attacks occur when a shark misidentifies a human as their prey. And though there has been a slight increase in the number of great white shark bites globally, the pattern is not due to increased aggression, but rather a combination of more people being in the ocean and a stronger emphasis placed on reporting bites and facilities.

“Sharks are actually important for the environment, and our focus here in the lab is to study both ecology and evolution, and especially the reproduction aspects of what are referred to as mesopredators: meaning those that are in the middle of the food chain,” Daly-Engel said.

“Sharks can go pretty much anywhere, and swim for thousands of miles, but what is amazing is they come into inshore bays and estuaries to give birth. These shallow waters have fewer large sharks to prey on baby sharks and provide plenty of great food sources for them.”

GLOBAL WARMING

Daly-Engel says sharks can go pretty much anywhere and swim for miles. Many can be found right here in the Indian River Lagoon,

a nursery for shark breeding. JEFF EBLE , FIT;;

Research on shark reproduction at Daly-Engel’s conservation lab focuses on how sharks are using these nursery grounds and the changes that could be affected by global warming.

“We know that climate change can affect populations of animals through extinction or by causing them to have to move, which lowers their genetic diversity,” Daly-Engel said. “This is important for population health so they can rebound following depletion. After looking at what types of climate effects may cause them to move their nursery habitats, we can model this information to develop predictions for what will be the critical habitats for future reproductive habitats.

“The proximity of the lab at Florida Tech — minutes to the Indian River Lagoon and the Atlantic Ocean — offers a unique opportunity to conduct field work right in our backyard. Florida Tech’s resources and the technology available here have been huge in helping us improve underwater monitoring and our understanding of climate conditions, meteorology and satellite data, which we use in our modeling.”

Daly-Engel made headlines in February 2018 for leading a research team that discovered a new deep-water shark species, the Atlantic sixgill. Just months after, she was among four authors whose research led to the discovery of another new shark species, Squalus clarkae, named after her mentor, Eugenie Clark, a female pioneer in shark biology. Otherwise known as the Genie dogfish, the newly identified species was identified from the Gulf of Mexico and western Atlantic Ocean.

“Eugenie was the mother of all shark biologists, and it was truly fitting that this new species was named after her,” Daly-Engel said. “Her work showed me that it was possible to make my own mark in what has been traditionally a male-dominated field.”

For Daly-Engel, whether in the lab or offshore gathering data, her mission to be a part of it all is because she loves what she does.

“I get to educate people about sharks, and help them understand, yes, sometimes they are scary,” she said. “But at the same time, they are interesting, unique, and most of all, important to our ecosystem.”

Want to help support shark conservation and learn more?

Donations made at fit.edu/giving/what-to-support/shark-conservation-lab/ go directly to help high school and university students in the FIT Shark Conservation Lab perform independent research, as well as travel to present their work to fellow scientists, natural resource managers and the general public.

Sue DeWerff Panzarino

Sue is an avid surfer, shark attack survivor and storyteller who loves to write about the wonderful people and great organizations on the Space Coast.